What Is A Mental Benchmark

Abstract

Benchmarking has been advocated by the Section of Health as a tool of clinical governance. The essence of benchmarking is learning from the best practise of others. Its ability to compare services and outcomes of intendance can facilitate change, ensuring quality command and continuous service improvement. The concept is in its infancy in the National Health Service despite its exceptionally rapid growth in business organisations over the past 25 years. Many of the characteristics that make the procedure and then valuable in business are equally relevant in healthcare. This article reviews the history of benchmarking and describes its awarding in mental health services for improving patient care. It includes an analysis of the centrality of the benchmarking doctrine to the cadre principles of clinical governance and reflects on the avails health services possess to facilitate benchmarking. It concentrates on the principles of setting up a team and uses a case example to highlight the organisational and clinical effect that a benchmarking project could have.

The concept of benchmarking was developed by the Xerox Corporation in 1979 and introduced into the Northward American corporate world in the 1980s. It continues to accept a wide application every bit a business activity, mainly considering information technology works. According to Reference Campsite and TweetCampsite & Tweet (1994), the Japanese word dantotsu, which means striving to be the all-time of the best, captures the essence of benchmarking. In fact, the Japanese pursued benchmarking in several forms well before Xerox. In a relentless search for excellence, Japanese companies would lend employees to, or swap them with, other organisations. This practice encouraged employees to become outside their workplaces, assess their own internal business processes confronting others and render with new ideas, systems and processes to facilitate the development of their own organisations. All the same, it would be deceptively simple and potentially misleading to try to distil a process as complex as benchmarking to such an elementary notion.

A more than formal definition, adjusted from that of the Xerox Corporation itself, describes it as 'the continuous process of measuring products, services and practices confronting leaders, allowing the identification of best practices that will pb to measurable improvements in performance' (Reference CampCamp, 1989). In the nowadays context, benchmarking has little to practise with setting benchmarks (i.e. providing measurement standards or references for others to run across or compare against), although some authorities even so invoke this concept in their definition (Department of Trade and Industry, 2004). Nor is its full potential existence wearied when it is used every bit a method for producing guidelines or national standards for patient care (Reference Bucknall, Ryland and CooperBucknall et al, 2000). Benchmarking in the National Wellness Service (NHS) is evolving simply slowly and is notwithstanding used mostly to appraise an organisation'south position in relation to other services, with little assay of the reasons for whatever gaps (Reference BullivantBullivant, 1996). This is certainly the case in mental health practice (Reference McGowan, Wynaden and HardingMcGowan et al, 1999; Reference Mirza, Green and LuyombyaMirza et al, 2003).

In an endeavour to make the concept more than generalisable in other spheres, Robert Reference CampCamp (1989) has reduced the definition to 'finding and implementing best practices'. This refinement alludes to a foundation that is not dissimilar to the framework underpinning evidence-based medicine, although the processes of evaluation of best practice are dissimilar. What is also different is the connotation surrounding the term 'best'. Whereas recently published evidence-based all-time practices for the treatment of schizophrenia (National Plant for Clinical Excellence, 2002) might exist an established and shared concept across different mental health services, the best exercise in the benchmarking sense for implementing that handling varies, fifty-fifty betwixt like organisations, depending on their own unique situation. Thus, the custom within benchmarking is to larn from the best practise of others (the chosen 'partners') and to empathise the processes by which performance can exist enhanced, rather than simply to copy another procedure. In some circumstances, what is best for ane organisation may be disastrous for some other, and in this article I try to depict the intricacies and pitfalls associated with undertaking a benchmarking projection. Several forms of benchmarking exist, and here I describe Reference CampCamp'south (1989) typology, which typically shows breakthrough results. Camp suggests that four types of benchmarking (internal, competitive, functional and generic process) should be carried out in the order listed beneath. Each has a specific outcome and benefit.

Types of benchmarking

Internal benchmarking

Internal benchmarking should be the starting point of whatsoever benchmarking process. It is usually necessary to document internal working processes first and internal benchmarking is the most straightforward way of accomplishing this. The partner should be within another part of the service, not as well geographically distant and should share like functions and processes. For example, information technology would be relatively straightforward to compare appointment booking for out-patients in different hospital departments. The contrasting procedures may reveal some best practices within the organization that can be modified and replicated elsewhere. Previous attempts at internal benchmarking have shown that exercise varies greatly from surface area to area. This can be as simple equally innovations in i ward being unappreciated on an next ward (Reference PattersonPatterson, 1993).

The advantages of internal benchmarking are numerous. As well as ease of data drove resulting from greater internal consistency, it is also relatively cheap and use of an internal partner tin bring to light potential problems in working with external organisations. Another advantage is that it should not be difficult to find partners within the NHS: internal benchmarking is a natural choice for hospital systems, every bit at that place are multiple sites inside a hospital and even multiple hospitals within a trust for comparing. It likewise allows sharing of comparative data and internal trends with departments within the service, assuasive the exploration and integration of multidisciplinary approaches to optimise processes and outcomes. Nevertheless, a limitation of internal benchmarking is that the level of the best performer within the arrangement normally determines the level achieved by the residual.

More specialised services may consider their work to be also sophisticated for benchmarking because of the futility of finding a suitable partner. This is ofttimes a error, as it should be possible to concentrate on benchmarking of more general processes. For instance, nearly psychiatric services, including specialised services, have strategies for managing substance misuse. Benchmarking these shows what a partner is doing differently and mayhap more successfully.

Competitive benchmarking

The principal aim of competitive benchmarking is to compare a specific process with that of the best competitor in the same industry and to place performance levels to exist surpassed. This is the stage after baseline attempts at internal benchmarking. Competitive benchmarking is of import because a progressive arrangement, in order to assess its strengths and weaknesses, must at some phase assess the gap between its ain operations and the competition. Occasionally, this procedure can be hindered if the competition is revealed to exist performing less well than you are.

Functional benchmarking

Functions of an organisation that are performed in other industries every bit well as in healthcare grade the basis of functional benchmarking. If the best partner operates within a unlike industry, the advantage of this type of comparison is that a mental health service attaining this level of benchmarking has the opportunity to improve operation beyond the best NHS or non-NHS competitor. For example, a mental health service should discover worth in benchmarking against institutions that have a reputation for consistent delivery of accurate and important information to staff, for example an airline service. Such an exercise could advance performance in shared similar functions, including providing customer satisfaction, data processing and risk management strategies. A disadvantage of functional benchmarking is that it does non focus on the processes of the partners. The lessons learnt might therefore be harder to implement because fifty-fifty though one is able to learn from the data processing function of an airline, transferring this noesis to a mental health service requires considerable integration.

Generic process benchmarking

Generic process benchmarking allows benchmarking of specific processes across different industries to find the best practices wherever they may be. For case, an armament manufacturer was able to produce smoother, shinier shells following consultation with a lipstick company. Senior infirmary managers seeking to amend income might concentrate on increasing revenue from their hospital'south avails by comparison against any company that is performing this procedure well. Reference SussexSussex (1999) suggests that benchmarking against h2o and electricity companies should be enlightening fifty-fifty though at first glance they seem incompatible with wellness services. He highlights their similarities: for case they are local monopolies delivering essential services and they are affected by significant inherited inflexibilities such as location, capacity and aged equipment. Their many similar generic processes offer the hospital opportunity for a large improvement in performance.

Outcomes

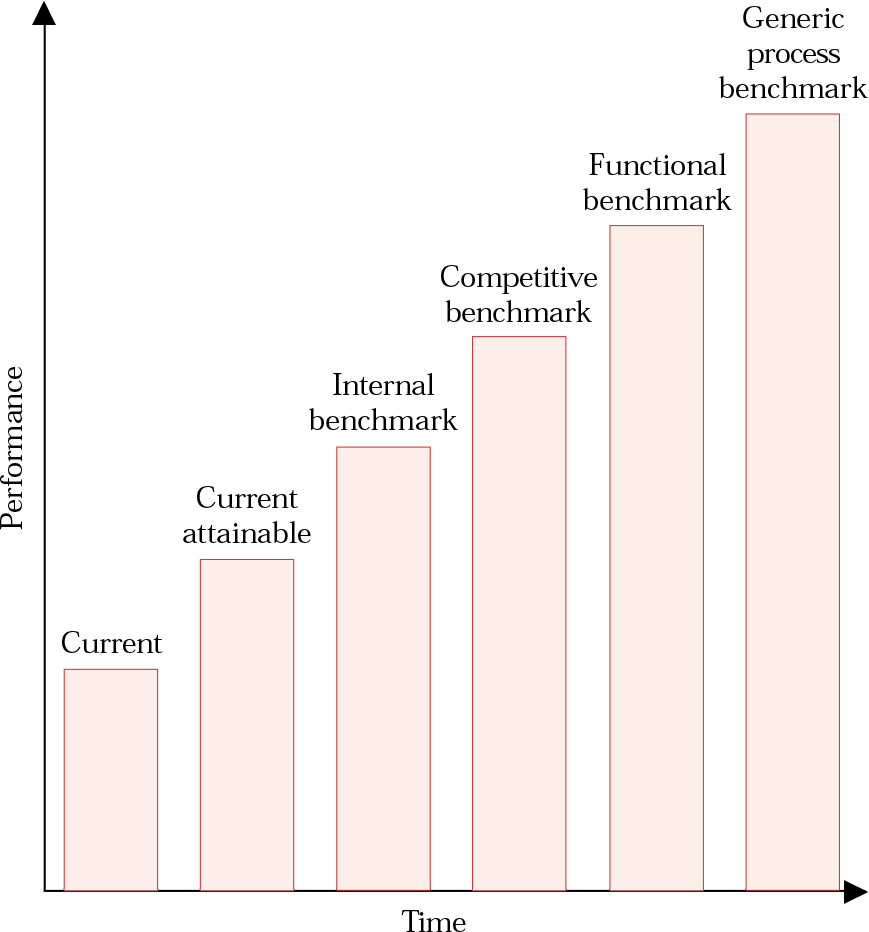

Figure one illustrates the potential improvements in performance that each of the four types of benchmarking produces. Internal benchmarking offers the least potential for truthful breakthrough improvement, although information technology is a low-risk way to acquire and practise the discipline. Navigating competitive and functional benchmarking requires more effort and resources, and their success depends on a greater familiarity with benchmarking methods. Generic process benchmarking is best-selling as providing the best results, but is attendant on the organisation having matured through a series of projects and should not be undertaken by novice organisations without skilled guidance (Reference Army campCamp, 1989).

Fig. ane Levels of attainment possible through benchmarking. Current attainable operation is that which could exist realised by making optimal utilise of existing avails. For each of the other performance levels the degree of superior functioning will be related to the extent of the pursuit of best exercise. Accomplishing the all-time performance will eventually entail benchmarking against institutions outside of healthcare.

Why should benchmarking exist applied to healthcare?

Relationship to clinical governance

Faced with however another quality initiative the sceptical clinician may be wondering what advantages benchmarking offers. The Section of Health has challenged managers with the responsibility of commissioning and providing efficient service delivery through quality improvement activities (Department of Health, 1997). It has recommended benchmarking as an activity that, similar inspect, well-considered guidelines and other systematic reviews of practice, tin inform the procedure of clinical governance (Section of Health, 1999). Clinical inspect by itself has been recognised equally having a poor tape in improving practise (Reference HopkinsHopkins, 1996). There is growing business that the wealth of guidelines impinges on inventiveness, fails to solve the problems of poor care and may in some circumstances fifty-fifty be harmful (Reference McDonaldMcDonald, 2003). Traditional measures of service use such equally infirmary readmission rates and length of stay often reflect service policy and provision in a self-fulfilling manner rather than giving true information nigh the bear on of treatment on patients (Reference ShooterShooter, 1997). Psychiatrists also see difficulties in making sense of experimental evidence to inform clinical controlling because of the small scale and short-term nature of near psychiatric trials (Reference Wykes and MarshallWykes & Marshall, 2004).

Benchmarking demonstrates several refinements over these other activities (Box 1), mainly considering its doctrine of continuous improvement is a central tenet of clinical governance. It is a ways by which the practices needed to achieve new goals are discovered and understood. Benchmarking tin can be seen as a direction-setting procedure that helps to manage the relationship between systematic policy developments, inefficient processes, identified clinical pathways and evidence-based outcomes. It moves abroad from the traditional method of establishing targets, the extrapolation of internal past practices and trends. Benchmarking does not restrict an organisation to the limited supply of internal ideas and performance assessments avant-garde past initiatives such every bit quality circles (Reference ColeCole, 1999). It also allows for potentially boundless continuing comeback by comparison against a wealth of medical and business organisations anywhere in the world. Thus, a mental health service can keep up with the rapidly changing external environment and reduce staleness associated with conventional goal-setting.

Box 1 Advantages of benchmarking

Benchmarking has advantages over other quality initiatives considering it is:

-

• practitioner led

-

• externally focused to augment practitioners' horizons of what is realistically achievable

-

• research dependent

-

• evaluated by measurable and climate-focused outcomes

-

• audited locally but comparable widely

-

• realistic within the clinical setting

-

• able to emphasise the need to support a change

-

• supported by immediately bachelor action-planning

-

• able to recognise individuals' efforts

-

• able to prevent the waste of resource

-

• able to develop practice, not just monitor and sustain existing practice

-

• comparable with other systems of how best practice is achieved

-

• aiming for the best achievable anywhere, not but locally or fifty-fifty nationally

It is of import to recognise that effective benchmarking is not a one-off exercise. Information technology is a standing procedure of improvement with the expectation that as ane do stops some other should start. Box 2 illustrates some of the mechanisms past which benchmarking may meliorate practice. Naturally, there are limits to the improvements that can be achieved and, potentially, to the ability of an organisation to use benchmarking effectively.

Box two Mechanisms by which benchmarking can amend exercise in healthcare services

-

• Spurring on private clinicians and whole units to be among the all-time may raise morale, which is of import to patient care and good service delivery. This more than positive approach may have greater success than did confrontational initiatives such every bit competition and contestability in the 1990s, which are widely perceived to have failed as stimuli for NHS trusts to provide services equally efficiently equally possible (Reference SussexSussex, 1999).

-

• Benchmarking allows users and carers to be involved in the process of change, orienting services to encounter changing user needs and focusing on key areas that require attention.

-

• Benchmarking is a natural tool for supporting and enhancing clinical governance by providing a constant bulldoze to raise quality through its various types.

-

• It allows the NHS to mensurate its services in terms of results that are of import to users. This may atomic number 82 to the development of more advisable measurement systems and institute realistic objectives that can exist easily implemented.

-

• It creates a better agreement of the dynamics and practices of expert health service functioning and of other non-healthcare organisations.

-

• Healthcare workers may prefer working in an atmosphere that fosters growth, breakthrough thinking, innovation and high standards, qualities that in turn may atomic number 82 to better staff retention and more consequent care of patients.

-

• Once identified, a best practice can exist hands shared between members of the same or other wellness services, who tin can extract elements useful to them.

-

• Benchmarking can lead to reduced costs for an establishment, enabling redistribution of coin for other aspects of patient intendance.

-

• Systems theory dictates that incremental improvements to an existing system or process are less successful in achieving exponential performance comeback than is redesigning and replacing it. Benchmarking encourages just such key change from outside the organization, rather than relying on potentially limiting ideas for improvements from within information technology (Reference Watzlawick, Wealdand and FischWatzlawick et al, 1974). Changes to systems are more likely to occur with functional and generic process benchmarking than with internal benchmarking.

Limitations of benchmarking in mental wellness practice

Information technology might be argued that benchmarking is a valid practise in mental health practice only if it produces an improvement in patient care. Use of a benchmarking team to improve an administrative or other support procedure is unsatisfcatory if there is no benefit for patient intendance. For case, pregnant expenditure on an industry-leading it system does not automatically lead to improved patient care (although that potential evidently exists). Worse, it may advisable money from an existing service that was providing useful and appreciated support.

There are other factors that limit the ability of a mental healthcare organization to use benchmarking effectively. First is the lack of practiced consequence measures for mental wellness services. Industrial companies tin measure improvements in terms of reduced or improved profits, whereas mental wellness benchmarking outcomes are likely to be more qualitative and may require more careful deliberation. If information technology takes a long time to determine measurable outcomes before setting upwards a project or too long (more than about 6 months) to complete, a project a squad can lose enthusiasm and support from inside the organisation. The same can happen if healthcare services spend a lot of time in search of ideally compatible facilities against which to compare themselves rather than taking a broader approach and learning from wherever they tin. Finally, initiating a project for the sake of undertaking benchmarking is commonly much more hard than starting 1 in an expanse where a specific breakthrough comeback has been long required (Reference Mosel and SouvenirMosel & Gift, 1994).

Box iii highlights some inappropriate uses of benchmarking.

Box three Inappropriate uses of benchmarking

-

• It is a poor use of resource for investigating matters of moderate-to-depression bear on

-

• It is a poor use of resources if it is only to exist used as an information-gathering technique

-

• Information technology should not but re-create the best practices of others

-

• It is not a form of competitive analysis

-

• Information technology should not be seen as a pretext for visiting interesting companies

-

• Information technology should non be viewed every bit providing a quick fix for problematic processes in psychiatric services. Even if an outstanding practice is found, it is likely that information technology volition have to be modified in gild for information technology to be made effective within one'southward own organization

What avails do healthcare services have for benchmarking?

Adapting benchmarking to the healthcare sector is no different in principle from adapting it to any other sector in which many dissimilar professionals with specialised functions work closely together. Reference Camp and TweetCamp & Tweet (1994) advise that most hospitals are relatively pocket-sized organisations when compared with large industrial enterprises. This should make information technology easier for them to communicate internally, make rapid decisions, question a breadth of staff and access extensive records that comprise much potentially valuable data (Reference LelliottLelliott, 2003). This has to exist balanced against the likelihood that they will have fewer full-time clinical staff gratis to carry out a benchmarking project.

Internal and competitive benchmarking require a relatively open commutation of information. Although this may well benefit both parties in the long term, the benchmarking partner may be more reluctant than the 'petitioner' to reveal its processes. Fortunately, the health service involves organisations that are more than prepare to share information. For example, at that place is a wealth of readily available information about clinical risk management from audits, complaints, incident forms and inquiries within each hospital which is oftentimes limited to within a trust. Benchmarking of the processes by which other trusts use data virtually errors and complaints to broaden functioning should be relatively straightforward owing to the degree of candidness that health services cultivate. Benchmarking relies heavily on an atmosphere of trust, and such easy access to information may non be manifest when mental wellness services outset benchmarking confronting non-medical companies, which may wish to protect their industrial secrets.

The following instance example is fictional but faithfully reflects clinical reality. Any resemblance to an actual case is purely coincidental.

Case example

Dr S, a general adult psychiatrist working in St Cuthbert'south district general hospital is dismayed past a complaint from the female parent of a patient. Her son has been on a waiting list for cerebral–behavioural therapy (CBT) for psychosis for x months. The clinical director of the service, who has an interest in benchmarking, convinces Dr S to review why the waiting list is unacceptably long.

Dr S forms a squad to map provision of CBT for psychosis (Fig. ii). It identifies a number of delays that generate an average waiting fourth dimension of 13 months. For example, a questionnaire reveals that that at that place is merely one psychologist available to provide ane session a week, whereas the waiting listing suggests a need for eight sessions a week. It also demonstrates that patients receive CBT for positive symptoms of schizophrenia but practice not receive handling for negative symptoms or poor social skills. The team members determine that, should they non detect a better solution, they might utilize inferior doctors and employ a part-time supervising psychologist to reduce the waiting list.

Fig. two Process map of the pathway for an in-patient to receive CBT for psychosis

A serendipitous meeting with a manager in the primary care trust highlights a service recently set up in a large forensic psychiatric unit of measurement ten miles away. It is within the aforementioned trust and appears to exist an ideal internal benchmarking partner.

The team visit the unit of measurement, and observe that the forensic service is using weekly group therapy to treat 31 patients divided betwixt three groups. Handling continues for 4 months, during which time it addresses social skills, and positive and negative symptoms. Six trained nurses and four trained psychologists run the groups. The six nurses also piece of work on the wards and supervise other nurses. The groups are repeated iii times per year and the average waiting fourth dimension to join a grouping is ii months.

The team members realise that they would never take devised such a scheme themselves. They adopt the practice in their own hosptial, providing similar groups on a smaller scale, and surpass their earlier goal.

The benchmarking practice resolved the two most significant problems that had resulted in the previous sluggishness: the limited number of costless rooms and a not-evidence-based belief that CBT had to be delivered individually.

Conducting a study

Many processes will appear suitable for benchmarking. It is recommended that people offset with a small project that can be performed within 3–vi months, for which a benchmarking partner is easily identifiable and where objectives are specific and measurable. Preferably the project should effect in improved patient care. It would be prudent to consider processes that users have said are inefficient, peculiarly ane in which the squad can identify a specific bulwark to providing constructive treatment for an identified demand. Table 1 offers a multifariousness of potential projects.

Table 1 Potential benchmarking projects in mental health services

| Aim | Benchmark |

|---|---|

| Improving treatment of resistant schizophrenia | An system that specialises in such treatment |

| Reducing average length of stay in seclusion | An organisation that does not have a seclusion room |

| Reducing prescription costs | A service with a record of depression costs |

| Improving cleaning of hospitals | An organisation such as a big hotel concatenation |

| Provision of excellent food in hospitals | An arrangement such as a high-quality airline |

| Improving electronic tape-keeping | An organisation with a substantial electronic database |

| Improving security on site | An armed forces unit or prison house |

The next chore is to identify key individuals to make upwardly the benchmarking team, as outlined in Box iv.

Analysis of internal practices

Having established the process to be reviewed, the squad should embark on an assay of the electric current practices inside it, using the tools of process mapping (Reference Lenz, Myers and NorlundLenz et al, 1994). This groundwork allows the squad to recognise steps crucial to meeting objectives, in addition to inefficient or redundant steps. Mapping is peculiarly useful in identifying blockages (e.g. the delays in Fig. ii), too as augmenting any hereafter comparison against external benchmarking partners when determining how they manage inefficiencies and impediments.

Box 4 Suggested key players in a benchmarking project

| The team leader | Plans the development of projects and relays information to the whole organisation virtually the squad's advancement |

| The benchmarking team | Team members undertake the majority of the project work and should ideally piece of work with or exist familiar with the process existence benchmarked |

| Functional experts | Valued for their appreciation of how the service functions and power to predict how modify to one office of the process will ultimately affect the residual of the service |

| Mental health users and carers | Add the customers' perspective, ensuring that the project does not issue in ineffective change |

| The executive champion | Preferably a senior manager, not simply taking responsibility for the project but likewise ensuring recognition of the team'due south work |

| The process sponsor | A manager such as a clinical managing director with a directly interest in the results of the projection and who has a closer interest in the process than the executive champion |

| Stakeholders | Although not involved in the benchmarking itself, their dissatisfaction with a service may help initiate the procedure; they are of import in setting limits for the scope of the study and ensuring that the objectives of the study are met |

It is appropriate to behave a airplane pilot report earlier proceeding to the full written report. This allows team members to familiarise themselves with the tools, modify their aims if necessary and, of paramount importance, encourages senior managers to support subsequently work on the basis of positive results.

Choosing what to mensurate within a specific process requires identification of the essential quantifiable stages of the process that are aligned most closely with the service'southward duties, aims and objectives. The selection might be based on counting patient complaints about a process as a judge of its success. If particular data cannot be used in achieving the specified improvement it is unlikely that they need to exist gathered. For instance, user satisfaction is often regarded as a basic measure out of service delivery. Even so, information technology may non exist much use every bit a mensurate if the objective is to reduce out-patient waiting times, because information technology does non straight reverberate any comeback in waiting times and is likely to be confounded past other variables.

Having identified the procedure and outcome measures, the adjacent footstep is to ostend current levels of success, using a well-designed questionnaire. The first stage in designing the questionnaire is to agree an objective for it to test. The questionnaire should also be able to excerpt information from the benchmarking partner to detect the mechanisms behind their best practices. Questionnaire development is a complicated process, and an internal pilot questionnaire can assist to rectify vagueness, eliminate jargon, ensure that the questionnaire asks the correct questions and add to the information already gathered almost the procedure in the organisation. Having as few questions every bit possible reduces the chance of alienating a benchmarking partner. Every question should contribute independently to realising the objectives of the study and not be repetitive or overlapping. Analysing the answers of the airplane pilot will betoken how well the questionnaire meets these objectives.

Identifying potential benchmarking partners and best practice

In parallel with the higher up is the search for partners, often based on reputation for excellence, similarities of service and willingness to share data. The presentation to the partner needs to exist intelligible, disarming and tested. Some of the key questions that help excerpt data from a partner are summarised in Box v. Most of a team'southward fourth dimension volition be spent on collecting information rather than meeting with the benchmarking partner, and squad members should not underestimate the amount of fourth dimension required to grasp the intricacies of their data systems, extract information manually from records and pursue missing data. The procedure is simplified if there is a convenient system for retrieving data, some assurance that the information are accurate and the capability to amalgamate the best practices of ane internal department with some other.

Box 5 Some questions to be considered when meeting with the benchmarking partner

With regard to the process nether report:

-

• How do you define its success?

-

• What qualitative measures define the excellence of the process?

-

• What quantitative measures define the electric current performance of this process?

-

• What is the cost-effectiveness of the process?

-

• What training is provided for the unlike personnel involved in the process?

-

• Accept whatsoever significant advances in performance been linked to particular improvements in the process?

-

• Is it possible to produce a map of the procedure?

-

• Is there whatever other information that might be helpful?

Best practice is determined to a large extent by how much of an impact the practice has on the business, the degree to which the results are related to specific goals and whether the practice dovetails with other programmes and operations already existence undertaken. For example, a system for dealing with service user complaints could exist subjected to functional benchmarking confronting the customer complaints process of a successful manufacturer that receives relatively few complaints and manages these efficiently. The low level of complaints may be related to the manufacture of efficient and reliable products. Nevertheless, splendid integration of the manufacturing process with the do of quick, satisfactory settlement of grievances leads to far superior performance, evidenced past even better sales.

Analysing information and modifying exercise

Assay of data should lead the team to enquire whether there are pointless or inconsistent practices causing loss of management or sluggish move and whether each correspondent to the process clearly understands the other participants' information requirements. For example, in a study optimising out-patient room apply, it might exist found that, compared with the partner, staff managing patient records in ane role of the edifice practice non know when clinicians require updated records in the clinic, or that the ship section underestimates the lead time necessary to convey patients punctually for their appointments. Knowing the cause of the discrepant practices between partners is only the beginning of the process because i then has to place the factors that propel those differences, such as variations in the use of protocols between departments, unreliability of suppliers, antiquated facility design or uneasy interdepartmental dealings.

Modification of practice is probable to be beneficial and lead to better performance when differences and the reasons for those differences between partners have been identified.

Careful consideration is required in implementation of changes, every bit healthcare benchmarking is fundamentally dissimilar from its industrial equivalent. It is important to ensure that potential comeback does not take on a purely competitive nature. If it does, quality of patient intendance may be sacrificed for speed of service or price savings. It is advisable to employ a technique such as the Plan, Practise, Study, Deed (PDSA) cycle (Reference Langley, Nolan and NolanLangley et al, 1996), which provides a framework for testing whether planned changes actually make the desired improvements before they are fully implemented.

A mastery of benchmarking is related to an understanding of its primal elements (Box 6). It besides requires the team to sympathise the relationships between all individuals involved in the process and to promote a cohesive and creative way of working. Without regard to the needs of these individuals, any changes that are fabricated may pb to increased tensions, fragmentation and discord. To avoid this, all findings must exist communicated on a regular basis to the parties that will have to implement the changes. This regular feed of information often induces more commitment to change, as resistance typically stems from the fear of loss of command. Box vii outlines some of the major aspects involved in managing change. Finally, any variation to processes should be made in collaboration with senior managers. Delivery from managers is vital to ensuring continuity, coordination, the involvement of relevant practitioners, removal of obstacles and access to sensitive data (Reference EllisEllis, 1995). Without sufficient support or authority, the changes suggested are unlikely to be implemented or to be effective.

Box vi The key elements of a successful benchmarking project

-

• A steering commission with an executive champion

-

• Guidance for the team members regarding the principles of benchmarking

-

• The back up of senior management

-

• Pinpointing with users and staff the important processes to investigate

-

• Analysing the individual steps of the process

-

• Choosing an appropriate outcome indicator

-

• An assay of internal functioning

-

• Pursuit of an appropriate partner

-

• Meeting the partner and analysing gaps in performance

-

• Modifying practise on the basis of the results of analysis

-

• Sharing the results of the project with all members of the organisation

Box vii The process of managing alter within benchmarking

-

• Place the organisational trouble that needs to change

-

• Identify dissatisfaction with the present situation

-

• Identify the steps required to change it

-

• Place exactly how information technology is going to bear upon on patient care

-

• Place the potential costs of the change

-

• Consider the consequences of not changing

-

• Create the desire for the comeback by involving stakeholders, users and carers

-

• Enlist back up from senior management

-

• Use a disciplined structured approach

Conclusions

The modernisation of the NHS requires the construction of frameworks for developing, testing and implementing changes that pb to comeback. This is still a major challenge. Benchmarking provides one such framework. It enables providers of health services to compare their operations against leading performers, to detect and implement best practise and to continuously meliorate the quality of care provided to patients. However, it requires a disciplined and systematic arroyo and, possibly more than importantly, time and resources.

Would benchmarking benefit the clinician? All healthcare workers encounter inefficient and wasteful processes within their service or receive complaints about the services that they work alongside. Benchmarking offers a way of understanding why those processes have become poorer and provides a source of innovative solutions that have been tried and tested. Benchmarking is challenging and requires dynamism and endurance in an loonshit where time and enthusiasm are deficient resources. Inevitably, it is likely to be undertaken past those who reject compromise and who have a relentless aim to exist the all-time.

MCQs

-

1 Benchmarking of a process:

-

a is the designing and implementing of benchmarks

-

b may assist in uncovering the worst practices

-

c may be undertaken with very piffling resources

-

d should be completed inside 180 days

-

eastward is a simple information-collecting technique.

-

-

2 Benchmarking is impeded past:

-

a staff awareness of the process being studied

-

b lack of support for the projection at each level of the organization

-

c difficulty defining suitable outcome indicators

-

d the sharing of information with other organisations

-

east a wealth of suitable partners.

-

-

3 Of Camp's iv types of benchmarking, internal benchmarking:

-

a should not be attempted commencement

-

b is difficult to accomplish within healthcare settings

-

c allows one to compare against the best in the world

-

d is easier because there are fewer barriers to information drove

-

e may issue in the collection of benchmarks.

-

-

4 Benchmarking has advantages over other quality initiatives because:

-

a the results of a benchmarking project are usually easily adapted within an organisation

-

b it seeks to heighten standards of a service to above the average

-

c in seeking all-time practice it is not express to looking inside the health service

-

d an identified best practice can be used by any number of similar organisations

-

east it identifies innovative solutions that have already been tried and tested.

-

-

5 The evolution of a adept benchmarking project is helped past:

-

a the setting up of a benchmarking team

-

b choosing a project that can exist performed at a slow pace

-

c considering projects that users have identified equally beingness beneficial

-

d prior work on a pilot study

-

e finding a partner against which to criterion.

-

MCQ answers

| 1 | ii | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | F | a | F | a | F | a | F | a | T |

| b | T | b | T | b | F | b | F | b | F |

| c | F | c | T | c | F | c | T | c | T |

| d | T | d | F | d | T | d | T | d | T |

| east | F | east | F | e | T | e | T | eastward | T |

References

Bucknall, C. E. , Ryland, I. , Cooper, A. et al (2000) National benchmarking as a support organization for clinical governance. Journal of the Regal Higher of Physicians of London, 34, 52–56.Google ScholarPubMed

Bullivant, J. R. N. (1996) Benchmarking in the UK National Health Service. International Periodical of Wellness Care Quality Assurance, 9, 9–14.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Camp, R. C. (1989) Benchmarking: The Search for Industry Best Practice. New York: ASQC Printing.Google Scholar

Camp, R. C. & Tweet, A. G. (1994) Benchmarking applied to health care. Periodical on Quality Comeback, 20, 229–238.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Cole, R. E. (1999) Managing Quality Fads: How American Concern Learned to Play the Quality Game. New York: Oxford Printing.Google Scholar

Section of Wellness (1997) The New NHS: Modernistic, Dependable. London: HMSO.Google Scholar

Department of Health (1999) Clinical Governance: Quality in the New NHS (Wellness Service Circular 1999/065). London: HMSO.Google Scholar

Hopkins, A. (1996) Clinical audit: time for a reappraisal? Journal of the Purple Higher of Physicians of London, 30, 415–425.Google ScholarPubMed

Langley, One thousand. , Nolan, One thousand. , Nolan, T. et al (1996) The Improvement Guide: A Applied Approach to Enhancing Organisational Performance. San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass Publishers.Google Scholar

Lelliott, P. (2003) Secondary uses of patient information. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment, 9, 221–228.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Lenz, S. , Myers, South. , Norlund, S. et al (1994) Benchmarking: finding ways to better. Journal on Quality Improvement, 20, 250–259.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

McGowan, S. , Wynaden, D. , Harding, Due north. et al (1999) Staff confidence in dealing with aggressive patients: a benchmarking exercise. Australian and New Zealand Periodical of Mental Health Nursing, 8, 104–108.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Mirza, I. , Greenish, D. & Luyombya, Yard. (2003) Benchmarking assertive customs treatment: a report from Waltham Forest. Clinical Governance: An International Journal, 8, 218–221.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Mosel, D. & Souvenir, B. (1994) Collaborative benchmarking in wellness care. Periodical on Quality Improvement, 20, 239–249.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

National Establish for Clinical Excellence (2002) Guidance on the Utilise of Newer (Atypical) Antipsychotics for the Treatment of Schizophrenia (Health Technology Appraisal 43). London: Squeamish.Google Scholar

Patterson, P. (1993) Benchmarking study identifies hospitals' best practices. OR Manager, ix (4) xi–15.Google Scholar

Shooter, Chiliad. (1997) What a patient tin can expect from a consultant psychiatrist. Advances in Psychiatric Handling, 3, 119–125.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Sussex, J. (1999) Cost benchmarking – utilities prove the way. British Journal of Healthcare Management, v, 265–267.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Watzlawick, P. , Wealdand, J. H. & Fisch, R. (1974) Change: Principles of Problem Formation and Problem Resolution. Norton: New York.Google Scholar

Wykes, T. & Marshall, Thousand. (2004) Reshaping mental health exercise with evidence: the Mental Wellness Inquiry Network. Psychiatric Bulletin, 28, 153–155.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

What Is A Mental Benchmark,

Source: https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/advances-in-psychiatric-treatment/article/benchmarking-in-mental-health-an-introduction-for-psychiatrists/1A0FDA45D70DC5182B40335C67E1D79A

Posted by: hillpoetastords1990.blogspot.com

0 Response to "What Is A Mental Benchmark"

Post a Comment